“Face of our Time” @ SFMOMA

So, I went to the SFMOMA this weekend, saw selections from their collection, the really fun “Art of Participation” show, and the works of four photographers, assembled under the title “Face of our Time.” (This is sort of a lead-in to a longer piece I’m working on about Susan Sontag’s On Photography (1977), which I just read all the way through finally, and Regarding the Pain of Others, (2003) which I just reread.

As much as Sontag exhausted me, I realized again in viewing these beautifully framed pieces how much her books changed the way I experience photographs (and thus, the world?), not to mention influenced many of the things I think about, in general and related to my artwork, about suffering, ethics, news, and responsibility. Mainly I thought about this fuzziness that arises in a few areas when we see photographs in museums, and Susan and all her judgmental temper and élan was fresh on my mind.

The featured photographers, Yto Barrada (b. 1971), Guy Tillim (b. 1962), Judith Joy Ross (b. 1946), and Leo Rubinfien (b. 1954), are “aligned” (according to the museum’s website) “for their shared interest in making pictures about the current condition of our world.” Okay, I think we can agree that all photographs are of current conditions; what the writer seems to be getting at is a kind of political bent in the works. In two out of four cases, this is a stretch. The website blurb, and the blurbs in the exhibition galleries, are trumping up the critical, political content of the works. (They also commit an easily avoidable sin, which is to refer to the “changing Africa“ that the South African Tillim is exposing—when in fact the photographs were taken in two countries, the DR Congo and Malawi.)

Guy Tillim. Rayina Henock and Masiye Henock. Petros Village, Malawi, 2006. from michaelstevens.com. (c) Guy Tillim.

Briefly, working backwards through the exhibition rooms, I found the Rubinfien pictures to be straight-up bad, grainy, frequently out-of-focus. Ross’s works, low-contrast, low depth of field, old-fashioned contact prints were beautiful, and while using antique cameras seems kind of gimmicky, it enhanced these photos by connecting them, in my mind at least, with portraits of political figures past, like Lincoln, whose images we see over and over. Tillim is an interesting inclusion because he is a photojournalist who has worked for major agencies and had major arty exhibitions (there are probably more of this species than I realize), and the work, 2 series, seemed to be a mixture of images I could see on a front page and those I’d imagine in a nice big book. I’m looking forward to learning more about him. I liked Barrada’s photos pretty well, and I think the blurbs did them and her a disservice by insisting that they depict a local culture being “disrupted” by tourists who are never pictured. Although there is undeniable political tension in the Strait Project, of which these photos are a part, I don’t think the politics are the defensive salvage ones the blurb hints at.

As I walked through the galleries, I found myself thinking a lot about permission and ethics related to authenticity related to what I’d call staginess, or the quality of being set up for the camera. Rubinfien’s photos clearly demonstrate disregard for permission to be photographed, and I was much more perturbed by that than by their supposed depiction of a new kind of fear we all live with (see how I’m interested in them as photos, not as reality. Thanks, Susan!). The photos are random “street shots” taken in cities around the world that have been targets of terrorist attacks in recent years. Some reviewers have called these photographs “portraits”; I think that is a gross overstatement, implying a level of consent and collaboration that Rubinfien is NOT engaged in. Only two of the photographs feature a subject looking at the camera, and many of the others are blurry or out-of-focus, with the signs of far zooming-in (things like nearer people’s heads and shoulders, some blocking most of the in-focus subject. I get that this is part of the aesthetic, but when that happens to one of my snapshots, I consider it a dud). Some of them are kind of creepy.

Leo Rubinfien, "At the Empire State Building, New York, from the series Wounded Cities. from sfmoma.org (c) Leo Rubinfien.

None of the titles give a name; rather, they are titled after the place where they were taken, as if these individuals and their particular concerns are subsumed by their location and its past. I don’t necessarily think this is native to photography as a medium, but this is what Sontag is talking about when she decries the importance wantonly bestowed on anything photographed and framed. Which is not to say that the anonymous people in these pictures aren’t important, but rather that mediocre snapshots are not made more worthwhile by being made large and glossy.

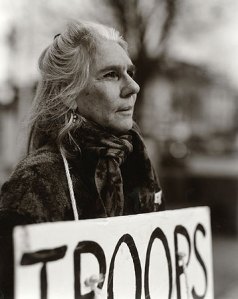

In the adjacent gallery were Ross’s dim, golden prints of Iraq war protesters in rural Pennsylvania, Ross’s home region. In great contrast to Rubinfien’s works, these prints are small (about 7 x 9″), posed, in a consistent format, and give most of the image to untrendy middle gray values. Their smallness and tone are some of their strengths; they ask to be looked at closely and long. They are unironic, emotional, tender, and thus really unusual these days. Some of the images really are dramatic and moving, and they have a realness in the way they come up slowly that blazing, fleeting snapshots like Rubinfien’s can’t begin to give. One wonders about these people in the Rust Belt, people whom we think of as the benighted yellow-ribbon-magneting supporters of the war, who are holding placards, and still holding them in 2006, when the photos were taken. Some of them, however, border on the goofily self-aware, and I imagine the photographer coaching, “okay, look into the distance, squint a little, good…” They are titled with the sitter’s name, “Iraq War Protester,” and town.

Judith Joy Ross. Susan Ravitz, Protesting the War in Iraq, Easton, Pennsylvania, 2006. from pacemacgill.com. (c) Judith Joy Ross.

So on one hand we have these portraits, respectfully taken, beautifully produced. But they stagnate, too staged, they become a little showy, and each one begins to blend into the next. On the other hand we have these street photos, which have a totally different energy, this spontaneity, but they’re almost not staged enough, in their quality and in their conscience. Which is unfortunate because Rubinfien is clearly motivated by conscience and empathy (not to mention anxiety), but I really find his practice as it appears unacceptable, and the more I think about it the more incensed I become that the work is received in galleries and museums. Not surprised, but bummed. I am convinced that this matters, and that Rubinfien is stepping on people as he blurs the lines between art and, well, not, and while this could be spun as bold and exciting, I find it a little troubling, grouch that I am. And I think: but what if his pictures were staged? Would we be disappointed? (Perhaps some of us would.) Would they be less real? (I don’t know, they’re still real people, posing for a photo about a real phenomenon.) Would they be more like art? (I think so.)

I have been thinking a lot about difference as opposed to representation. If a photo was about the political/ economic realities of the subject, but was yet fictional, then I wonder whether we talk about it as a differentation / elaboration / intensification of that political reality, rather than a representation of some fixed fact. I like this because it makes room for an art that can find its own momentum and be responsible to the lived. I find myself increasingly suspicious of the assumption that art is representation at core. Could we not rather see it as a growth of relationships.

Dana, I agree. It’s useful to think of understanding and seeing as the work of constructing rather than receiving. In a very abstract way art demonstrates human agency, possibility, and the malleability of the world. It seems to turn naturally towards the future and the imagination. In a less abstract way it perhaps demonstrates a kind of meeting the real world halfway – the world comes at us and we project onto it.